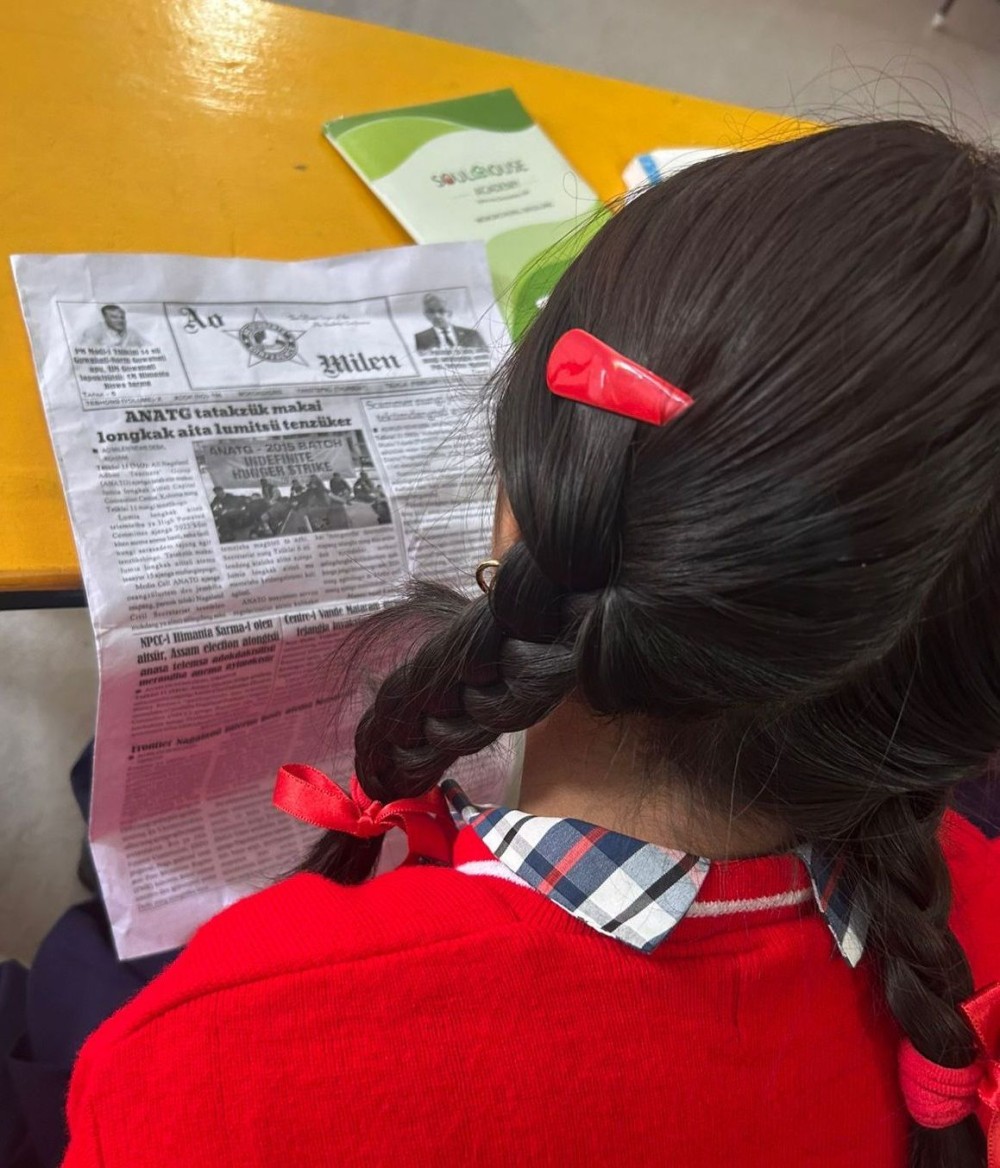

A student of Soul House Academy, Mokokchung reads Ao Milen, an Ao vernacular newspaper.

Yarden Jamir

Mokokchung | February 22

Concerns are growing over the future of the Ao Naga language, as educators, parents and language institutions note shifting linguistic habits among youth, the rising influence of English and ongoing challenges in language education. Despite community efforts to preserve the mother tongue, the challenges continue to daunt its survival.

The struggle to speak Ao

Observers say the declining fluency in Ao among younger generations is perhaps linked to reduced use of the language within families.

Publishing Head of Ao Riju (Ao Academy), Temjen Tzudir, told The Morung Express that a 2010 UNESCO report identifying Ao as an endangered language served as a critical wake-up call for the community. The classification came as a “shock” and prompted renewed focus on preservation efforts.

According to Tzudir, one of the key reasons younger children struggle with the language is that their parents often lack proficiency in Ao themselves. He also pointed to hurdles, including a prolonged debate within the community during the 1980s over language uniformity, which led to declining public interest. The issue was eventually resolved when the Ao Senden asserted that no single group owned the language and subsequently established the Ao Riju (erstwhile Ao Senden Literature Board) around 2004-2005.

Since then, he said, the language has witnessed steady progress, including efforts to standardise spelling, and has achieved around 80-90% uniformity.

However, the challenge of transmitting the language at home remains acute. Dr Lipokrenla Jamir, a mother of two, shared that her family primarily communicates in English and Nagamese. Her children have become more comfortable with English due to constant exposure to digital platforms.

While acknowledging that language is central to cultural identity, she admitted that limited parental fluency and a lack of consistent effort have made teaching Ao at home difficult.

Classroom realities & educational challenges

Teachers say the impact is reflected in the classrooms. Amenla, an Ao language teacher at Eden Academy, Mokokchung said while many students understand the language, fewer speak it fluently as they do not use Ao at home. English has increasingly become the primary language of communication between parents and children, she observed.

“The main problem stems from home,” she said and asserted that speaking the mother tongue at home would significantly strengthen language proficiency.

While current textbooks offer some foundational support, she emphasised the need for teaching materials focused on daily conversation and practical usage. To bridge this gap, Amenla said she often supplements prescribed lessons with basic translations and encourages students to converse in Ao among themselves.

According to her, an estimated 70-80% of students recognises the importance of learning Ao and takes the subject seriously, though some continue to struggle. She also observed increasing code-mixing with English words is common in everyday speech.

At the higher education level, the challenges persist. Toshisangla, Head of Department of Ao at Fazl Ali College, said that even core students often lack strong language proficiency. Despite some interest in the subject, she pointed to a decline in enrolment for the honours programme - from 51 students in the first batch to 32 in the second.

She attributed this drop partly to structural issues, including the absence of postgraduate programmes in Ao, which creates uncertainty about future career prospects for students. Additionally, she highlighted academic difficulties arising from the compulsory study of English literature and linguistics alongside Ao, particularly for students from rural backgrounds who possess good oral skills but limited exposure to English.

Toshisangla also raised concerns about inconsistencies in spelling at the school level, noting that the lack of emphasis on standardisation poses challenges in higher education. In some cases, students opt for alternative subjects to achieve higher academic scores, she added.

Despite these challenges, Toshisangla expressed optimism stating, “Language would continue to grow steadily and not become extinct.”

Preservation efforts

Language institutions, on the other hand, point to ongoing efforts to strengthen Ao.

Tzudir highlighted the impact of Arangtet, the Ao Proficiency Examination, noting that over 600 individuals including linguistics scholars have cleared it so far, helping standardise the language and generate interest.

He observed that most Ao publications are religious and mostly read by older generations, expressing concern over limited reading habits. He urged young linguists to develop academic and classroom-oriented materials. He also acknowledged the role of the Ao Baptist Arogo Mungdang and other community organisations in promoting the language.

A collective action

Stakeholders stressed the need for a collective, multi-pronged approach to preserve the Ao language for future generations.

Tzudir emphasised the role of community institutions, urging church leaders to deliver sermon in proper Ao, parents to speak it at home, and community members to use it consistently in social and cultural gatherings.

Parents called for conscious efforts within families and suggested educational institutions and language bodies to develop accessible learning methods, especially for children from mixed linguistic backgrounds.

Educators highlighted the need to strengthen teaching materials and promote everyday use of the language in and out of school.

All agreed that coordinated action among families, schools, and community institutions is essential to ensure the continuity of Ao language.