Rows of cabinets with pinned insects, beetles and moths, wings and carapaces at Museum of Entomology, FAC has turned classroom collecting into a biodiversity hub. (Morung Photo)

Yarden Jamir

Mokokchung | October 17

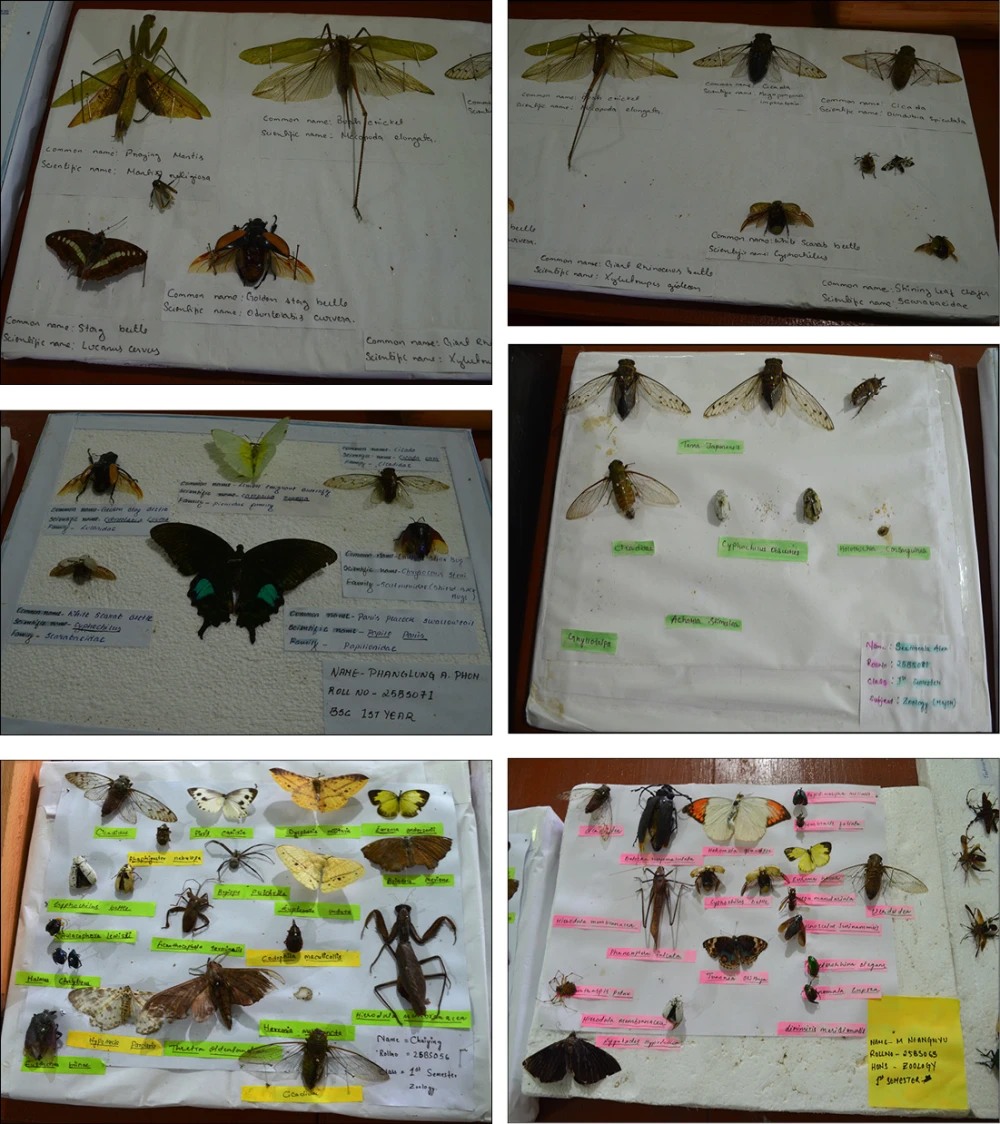

In a quiet corner of the campus of Fazl Ali College, Mokokchung, thousands of preserved wings shimmer under glass. Inside one of the college buildings, a locally crafted display structure, unassuming in appearance, holds rows of glass cabinets in which pinned insects, beetles and moths, delicate wings and armored carapaces, sit like a library of small lives. Student-made dioramas and hand-drawn labels stand beside specimens prepared in the college lab. Sparse in resources yet rich in curiosity, the exhibit forms the heart of a bold experiment: the Museum of Entomology (MUSE), an initiative that has turned classroom collecting into a nascent biodiversity hub.

“The idea was there for a long time,” says Imlinungla, Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Zoology at FAC. For years, students brought specimens to practicals, a by-product of fieldwork embedded in the curriculum. But the college lacked space and funds; many samples were discarded. “Now that biodiversity has become such a hot topic,” she said, “we thought it would be very good if we can restart storing and preserving [them] and make it into a biodiversity hub.”

What began as a course exercise has become a multi-pronged endeavour. Since Imlinungla assumed the headship last year, she has pushed the idea forward with the support of Principal I Wati Imchen and her colleagues. The museum’s display structure was locally built and funded through student practical fees, with the principal’s direct assistance for materials and construction. “When the idea came, I was more than willing to help them,” Principal Imchen later told this journalist. “We are moving very fast now.”

An interdisciplinary ambition

MUSE’s mission, ‘to connect entomology with wider ecological, cultural and epistemological frameworks,’ reads like an invitation to think beyond taxonomy.

For Imlinungla, the museum is as much an intellectual experiment as a collection. “I want this not just as part of the zoology department. I would want an interdisciplinary approach,” she explained.

Her interests bridge unexpected fields: culture, philosophy, religion, art and literature. She imagines local elders and artists telling insect stories; philosophers asking questions about life and consciousness through the lens of arthropods; and literature workshops exploring insect imagery in local and global texts.

“We are insect-eating people,” she says of the Naga community, referencing cricket and other entomophagy traditions. “But whether that insect has any relevance in our culture — that is something I would really like to know.”

Student energy has been central. What began as optional collection assignments turned into an outpouring of curiosity. “Even those classes which I have not asked to collect, they themselves are bringing it,” Imlinungla said. Minor students, not even those majoring in zoology, began arriving with specimens, sketches and ideas.

The department transformed these projects into a public exhibition, and students responded with dioramas and models that now form the visual heart of the museum.

Teaching, hands-on

The pedagogical value is immediate and tangible. Specimens are more than display objects; they are teaching tools.

“When we show them a live specimen, they become more clear about how different morphological structures are,” Imlinungla said.

The department plans student-led projects on animal behaviour, pollination, decomposition ecology and art-science collaborations.

The college’s aviary, another locally built structure supported by a shared inter-departmental lab-development fund reflects the same spirit of resource pooling that sustains the museum and will anchor studies on animal behaviour and breeding cycles.

For students, the museum turns abstract classification into tactile learning.

Imlinungla recalls training students to communicate with rural audiences, pruning scientific jargon into plain Nagamese, Ao and English so villagers grasp the ecological roles of species.

A recent outreach trip brought microscopes and zoonosis-focused talks to a village under the One Health banner, pairing veterinarians with students to discuss the interconnected health of people, animals and the environment. The villagers’ positive response confirmed that the museum’s impact can extend beyond campus walls.

Scale, limits and preservation science

The collection’s breadth already surprises visitors and faculty alike. Imlinungla estimates the holdings encompass roughly 300 genera, implying thousands of specimens.

But major scientific hurdles remain. The department lacks entomological specialists to identify many specimens to species level.

“Species level will be very, very difficult for us unless we outsource it or bring somebody expert for it,” she said, pointing to the need for taxonomic keys and DNA analysis.

Infrastructure gaps are more pressing. The museum battles mould and humidity; ethanol and acetone for specimen preparation are costly and scarce; and an ideal freeze-dryer, a machine that preserves specimens without internal ice-crystal damage, remains out of reach.

“If we can get that, if we can control the humidity, then it is good,” Imlinungla said.

Her team currently relies on ethanol washes and constant cleaning, a labour-intensive workaround.

Funding is a recurring theme. The department uses practical fees and the 20 percent common lab-development pool for essentials such as the aviary and other small purchases. Beyond that, there has been no external government funding specifically for the museum.

“We are working without any funds,” she said bluntly. “To work in that environment is very, very difficult.”

Regulatory and partnership puzzles

Ambition met bureaucracy when the department sought to expand the aviary into a wildlife and rehabilitation facility. Early discussions with the Forest and Wildlife departments seemed promising, but the approval process slowed.

Officials later clarified that housing local birds required central-level permissions under the Wildlife Protection Act, limiting the college to exotic species.

The setback nudged the team to pivot: the aviary will continue for behaviour studies and education rather than rehabilitation for now.

Still, partnerships are forming. The Veterinary Department has signed a memorandum of understanding with Fazl Ali’s Zoology team to support student internships, dispensary access and collaborations in poultry, dairy and animal-health programmes.

A small apiary supported by the Nagaland Bee and Honey Mission has already delivered training and a starter colony despite an early infection. The department plans to restart it with improved protocols and to host beekeeping workshops next year.

Community and institutional affirmation

FAC Principal Imchen frames the museum’s growth as evidence of a changing academic atmosphere. “All of the departments, especially science, are energised,” he said, noting that Fazl Ali aims to open its labs to neighbouring schools and encourage inter-departmental exhibitions.

The museum along with Chemistry and Botany displays has already become the third major exhibition the college has hosted this year. Imchen envisions regular, even annual, science expos drawing students from across the district.

Public response has been unexpectedly strong. Imlinungla expected only a few dozen visitors; instead, numbers swelled as word and social-media images spread. “The response was overwhelming,” she said, smiling. “Seeing is different from hearing.”

A careful optimism

There is urgency in Imlinungla’s voice when she recounts the practicalities: mould clean-ups, supply expenses, staff shortages a lab-assistant vacancy remains unfilled and the worry that future HOD rotations might alter the project’s momentum. Yet she remains resolute.

“If we can do without any kind of finances and things like that, just supporting each other… then I think this should not die down,” she said.

Her vision is as much about culture as it is about specimens. She hopes the museum will produce local research, a reference book based on their cataloguing efforts, and public dialogues that recast insects as ecosystem partners rather than mere nuisances. “At the heart of our museum will be our scientific thought,” she said, “but at the same time reaching out to society and letting them explore their imagination.”

The Fazl Ali project is, in its way, a lesson in incrementalism. What began as a collection of student finds once threatened by neglect and lack of space has become an institutional experiment in education, community engagement and cultural inquiry. With more funding, specialist partnerships and conservation-grade equipment, the museum could expand into formal research and species-level cataloguing.

For now, it thrives on curiosity, improvisation and the quiet confidence of a small team determined to keep the tiny lives in their cabinets telling bigger stories.