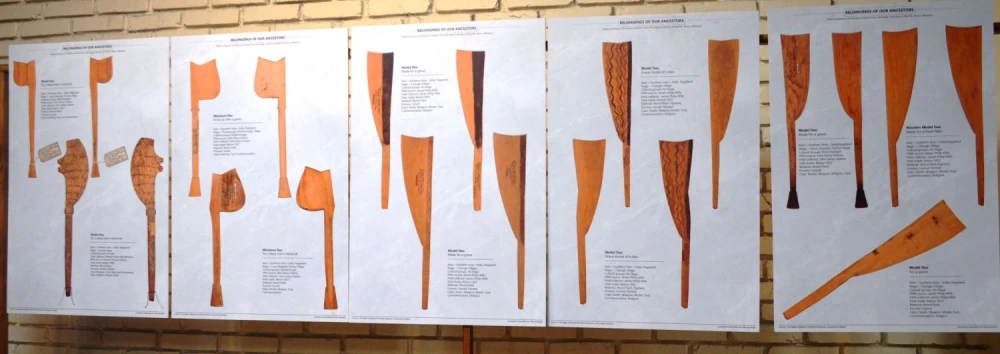

‘Belongings of our Ancestors’: Photo Exhibition of Funerary Artefacts from the Naga Collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum. (Morung Photo)

Morung Express News

Dimapur | September 10

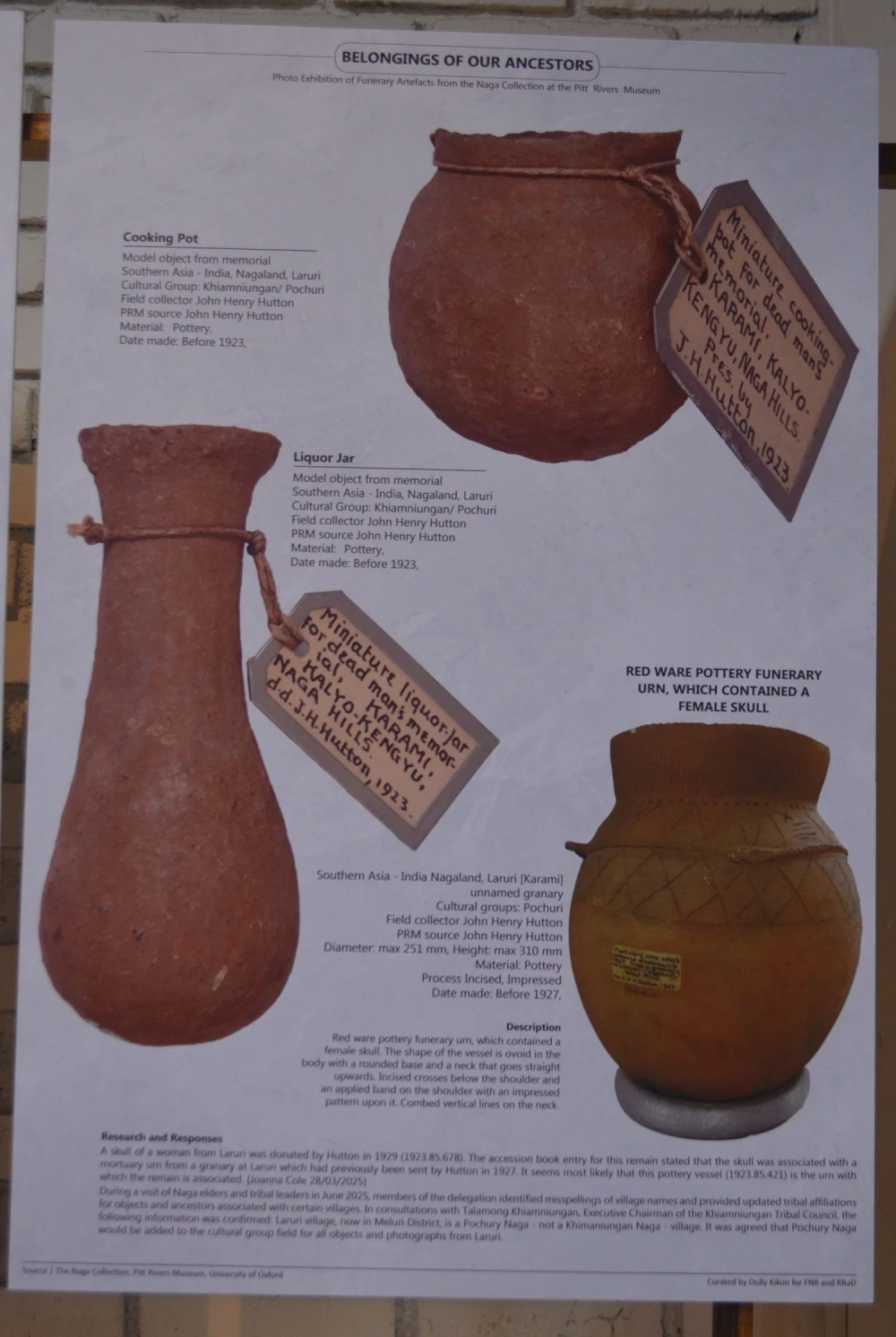

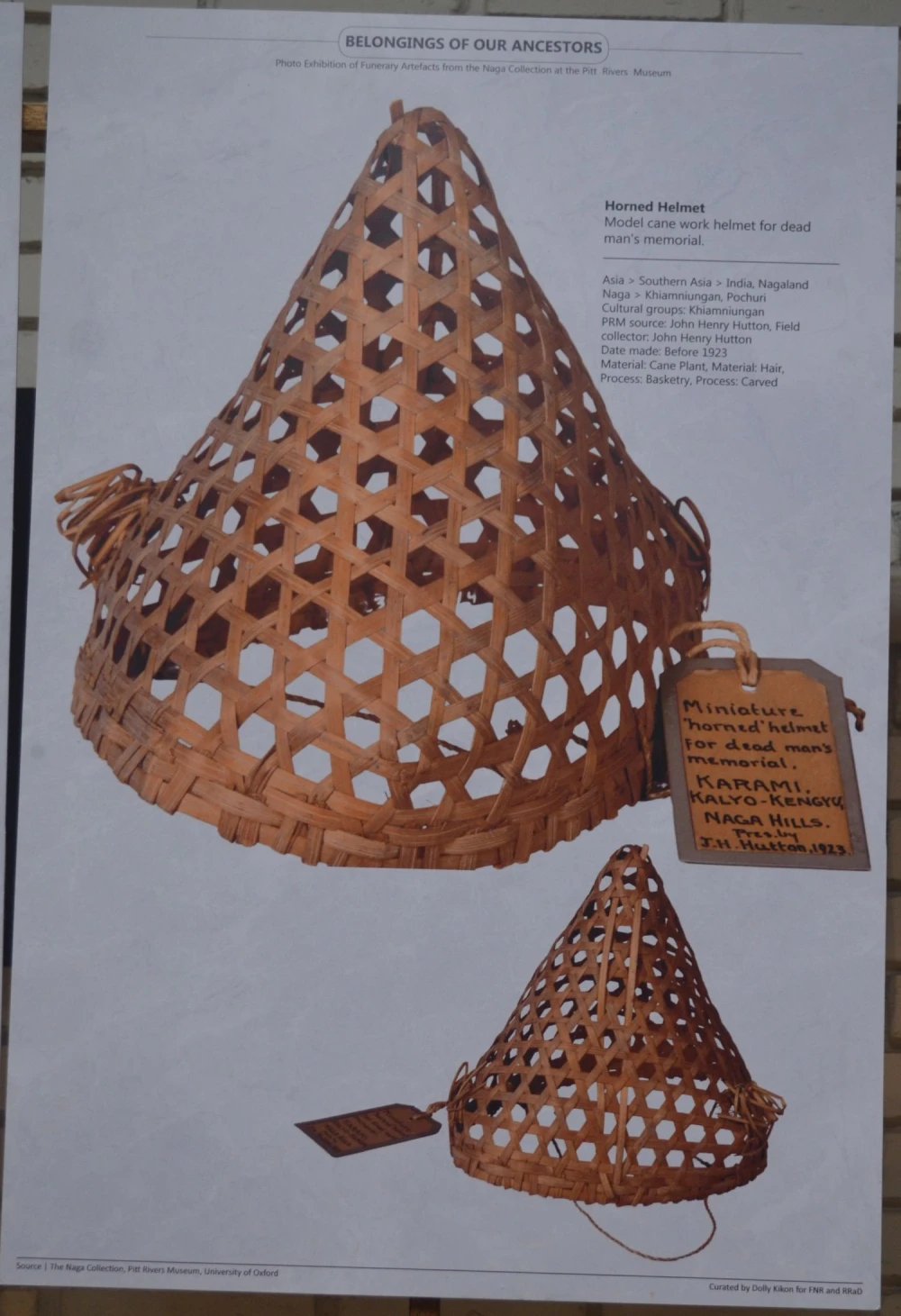

A photo exhibition is challenging the long-held colonial narratives by showcasing sacred funerary artefacts taken from Naga graves, presumably, without the knowledge of the family members and community. Titled “Belongings of our Ancestors,” the display features objects from the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, collected during the British imperial era.

This exhibition is a significant intervention in deepening the dialogue around the Naga colonial experiences. It throws light on the appropriation of funerary and personal objects from Naga graves, bringing this previously unknown history into the public domain. This exhibition is a form of truth-telling, which is essential for any healing process.

It counters the stereotype of their ancestors as mere “savages” by revealing intricate burial rituals that demonstrate profound care and respect for the dead. Crucially, the exhibition uses the collectors’ own notes, which admit that removing these items was a forbidden cultural taboo, to tell a story of loss and the ongoing journey toward reconciliation, healing and return.

‘Belongings of our Ancestors’

Curated by Dr Dolly Kikon, a Naga anthropologist, the “Belongings of our Ancestors” exhibition was put up by the Forum for Naga Reconciliation (FNR) and Restore, Recover and Decolonise (RRaD) for the September Dialogue held on September 6 last in Dimapur, Nagaland.

The artefacts on display tell a reflective story. As part of the Naga repatriation process, the visit by a Naga delegation to the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum in June 2025 provided, for the first time, a comprehensive view of the deep care with which Naga ancestors buried their loved ones.

“Besides looking at and praying for the ancestral human remains, one thing that caught our attention were also the belongings of our ancestors,” Dr Dolly Kikon shared.

It is crucial to be specific; these were not merely collected artefacts. They were belongings of Naga ancestors taken away from their graves.

“For us, this is deeply significant,” emphasised Kikon. She noted that these items provided the Naga people with their first ‘tangible glimpse’ into ancestral burial rituals, revealing the immense love and respect their forebears invested in laying their loved ones to rest.

“For long, we believed that Naga belongings taken away by the collectors and colonizers were given willingly as gifts,” said Kikon. “We now know that is incorrect.”

This exhibition definitively challenges that narrative with evidence from the collectors’ own records. An object presented by J.H. Hutton in 1915 is inscribed with his own description: “Placed over grave of a warrior… It is genna to move these.”

The term genna means a sacred taboo. To move these grave markers was an act of disrespect to the spirit of the deceased. Hutton himself documented this prohibition, acknowledging its cultural weight. The painful irony is that he recorded this taboo even as he violated it, removing the object from a warrior’s grave and sending it to the museum.

“Our ancestors believed that items given to the dead were sacred and should never be disturbed. To touch them was wrong,” Kikon maintained.

“This history underscores the critical importance of our ongoing mission of care and healing, led by the FNR and RRaD,” she emphasised.

A beginning of healing…

Ultimately, this exhibition offers a true glimpse of the Naga past, where our ancestors deeply cared for one another and honoured their loved ones with dignity even in death, she added.

She hoped that FNR and RRaD will continue to put up this exhibition in the office or a public space.

The Naga scholar highlighted the “healing” experienced by the people upon reconnecting with belongings of their ancestors. Kikon stated that for generations, Nagas were told over and over again that their ancestors were “rebellious, savage, and just headhunters,” which she called “conditioned inherited ignorance.”

“That is not true,” she asserted.

She emphasised that witnessing the intricate crafts and the “gesture of love” embedded in their ancestors’ burial practices challenges this painful history.

Referring to the exhibition of belongings taken from graves, she termed the experience a corrective to historical trauma. “When we see the crafts and gesture of love that our ancestors practiced, I think it brings a deep sense of joy, calmness, and also healing,” Kikon said.

“Today, we can actually look at the future and say, we had a past where we honoured one another. And that is truly a beginning of a healing, I believe.”