Abraham Lotha

When foreign tourists sign up to visit Nagaland to experience cultural tourism, their first choice of place to visit within Nagaland is usually Mon district to see the exotic Konyaks in their unspoilt natural state (‘Naked Nagas’) popularized and romanticized by anthropologists such as Fuer-Haimendorf and Hutton in the early part of the 20th century. For me, I had heard much about the Konyak Aoleang festival and boundary insanity like the one at Lungwa. So I decided to visit the area during the Aoleang festival with these interests in mind.

From Dimapur, I took the Sumo taxi. I had seat number ten and that meant we were packed like sardines. The old man on the extreme left of the back seat played traditional Konyak songs on the cassette recorder that he had been carrying very carefully. Two men explained the social context of the songs. “In the old days, unmarried girls would gather in the dormitory in the evenings. Then young men would come and serenade and try to woo their lovers. Men also sang songs to each other, but most often it is to the young women that men come and sing to win the love of the young girls,” they explained to me. Then the older men in the Sumo teased the two girls who were sitting in the middle row. Some lovemaking innuendos were also said in reference to the songs. Everyone joined in the laughter. The girls took the jokes in good spirit. “Nowadays, the deacons in the churches have banned such behaviours and as a result, it doesn’t happen anymore,” said one of the travelers. “Those days were satan days,” commented another. “But what is happening now is even worse,” he added. So I remarked, “Now it is double satan.”

I didn’t know what to expect in Mon. It was 17 years since my last visit. Unlike last year, there was no common Aoleang celebration at Mon this year. Instead, people were having celebrations in their own colony. So I decided to see the celebrations in different villages. I chose Lungwa and Shangnyu.

The road to Lungwa was better than I had thought. There were lots of road construction works going on along the way. Most of the vehicles we met on the way were trucks belonging to the Border Roads. Except for a few spots, the major stretch of the road to Longwa is mettled. At some places the BSNL people were laying fiber optic cables. It took us two hours and twenty minutes to reach Longwa.

As luck would have it, when we turned into the village, there were many people gathered in front of a house. I thought the Aoleang celebrations were going on. But, no, they were about to pull the new logdrum up to the morung above the road. All the men folk seem to be involved in pulling the logdrum. I was excited. This is only the second time (the first time in Chomi) that I have taken part in pulling a logdrum. I introduced myself to the people and they were very welcoming. Some of the kids saw me with the camera and they said, “Foreign, foreign.” “Nai, Kohima pura ase,” I told them. I took plenty of photographs. Finally when the pulling of the logdrum began, I also joined for some time.

It would take another few hours to get the new logdrum into the morung so I decided to see the morung. In one corner, a few people were busy cutting meat and cooking. So, here was some remnant of traditional culture still being practiced by the people. The morung was still being used. I was glad to see the woodcarvings inside the morung even though they were less than I had expected. Naga woodcarvings have been of interest to me so I was glad to see the woodcarvings in places where their symbolism and meanings are alive. One person came and asked me if I had seen the carvings outside. He took me out to the eastern front of the morung where there was a huge woodcarving piece. It was shaped in a curve with many symbols engraved on it. Mistaking me for an antique dealer, the man, Mancham, told me that the village was going to sell that woodcarving piece. I asked him who was going to buy it, and how much they were willing to sell it for. He didn’t tell me the price. Should that piece be sold? I asked myself. Why shouldn’t they keep it in the morung even if it rots away? Or would it be better, instead, to preserve it in a museum or other institution?

Then I went to the Angh’s house. His name is Longam Konyak. Some of his family members were there smoking opium when I went in. After about five minutes, the Angh came in. I greeted him. “Don’t go empty handed when you go to meet an Angh. It is our custom,” my Konyak friend from Mon town had instructed me. After giving him the small gift we sat down and chatted – about the village, his household.

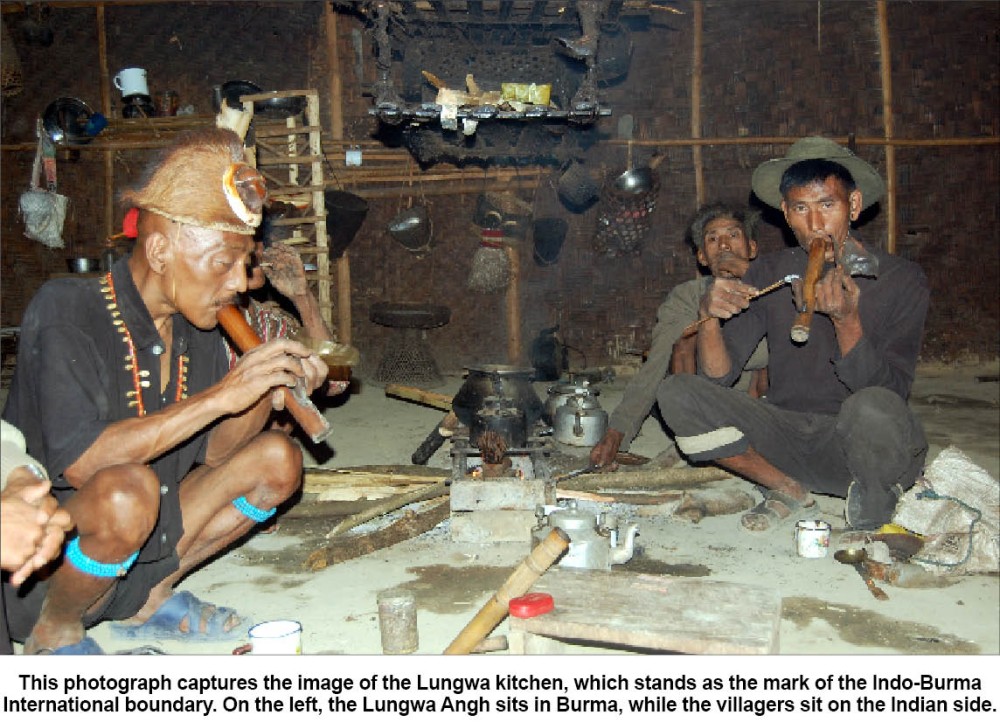

The best example of British arrogance and insanity (also not understood by India and Burma) is the arbitrary border drawn between India and Burma. The border between India and Burma runs through the entire length of the Angh’s house. The hearth and the pillars in the middle of the house divide the house into India and Burma. It is ridiculous. More Nagas should visit this place to see how Nagas were not consulted by a colonial power in the mappings of nations.

I then proceeded to meet the Deputy Angh, who is also the Chairman of the village. It seems he had been waiting for me but by the time I reached his house he had left for Mon for an urgent meeting but he left word with his men for me to sleep in his house. As I had to get back to Mon, I went and joined in pulling the logdrum for sometime and then returned to Mon.

Next I visited Shangnyu. The main celebration for the Aoleang festival was to be held that day. Because of that many were dressed in the traditional attires. We passed by one of the houses where a man was getting dressed. He wore a nice necklace so I asked him if I could take a photograph of him. “Yes, but you give me money” he said. I told him, “You are dressing for a festival and it is not a Naga custom to charge money for a photo during a festival” I told him. He finally allowed me to take his picture after someone in his group admonished him.

We proceeded towards the playground. One boy of about 9 years old brought a necklace with wooden skulls and wanted to sell it. “Five hundred rupees” he shouted. Immediately I knew that this kid learned this from the tourist culture.

We then passed by one of the morungs. I decided to go in and have a look. There was nothing spectacular or unusual about the morung. The usual logdrum, a few carvings on the beams but other than that, the morung was not even traditional because it was constructed in concrete with tin roof. As I was taking a picture of the logdrum, one man came and said, “The morung in charge said to pay Rs. 100 or Rs.200 for taking picture of the morung.” “But I am not a foreigner. I am a Naga and have come to see your village and your festival,” I told him. “Then you can collect from the foreigners and give us,” he said, mistaking my friend from Darjeeling for a Western tourist. “But there are no foreigners” I replied. I had been to other Konyak villages and been inside many morungs, and people were very happy to show us around the morungs; in Wangti the villagers even beat the drum for two different styles of beating. But I had never encountered such cheap commercialization of Naga culture as in Shangnyu. So I walked out of the morung with a bad taste.

As we went to the site of the famous woodcarving piece, the escort told us to meet with the Angh, explain the purpose of our visit, and pay some money for the upkeep of the heritage museum. The Angh was not feeling well so we only met his wife. After signing the register, the Angh’s son took us to see the famous woodcarving. We signed the register and were taken inside the museum.

The Shangyu sculpture, a huge and unique piece of woodcarving measuring about 18 feet long and 12 feet tall at the top end is attributed to a mythical man called Honnu. He had exceptional skill in hunting and carving and he attributed the skill as a gift from god. Since Honnu did not like to work in the fields, his father banished him to the forest. And it was in the forest, helped by some supernatural beings, that Honnu carved this sculpture.

The woodcarving piece itself is very impressive. It stands about eighteen feet long and at one end about twelve feet tall, all carved out of a single piece of wood. Engraved on the wood are replicas of two rainbows, two gibbons dangling from the branch of a tree, some human heads, a snake, a cock, replicas of two tigers (one of them only the lower portion of the body), a woman (in heat?), a couple making love, two warriors with erect penis that are bigger and longer than life size ones (they are apparently the star attraction among the engravings), and a few one or two other figures that are difficult to decipher, and on the other side, a miniature wooden vat, and some human heads. There are also other artifacts in the room such as brass gongs, mithun heads, buffalo heads, wooden figures, even an Angami headdress, two elephant tusks, a big gun, and some antique daos.

Apparently Shangnyu village is getting many foreign tourists who have more money than domestic tourists, and the villagers, including the kids, are developing the bad habit of asking money for anything. It is true that some tourists don’t have any respect for local people. When they see an ‘exotic’ Konyak, they will go up to the face of the person and click, click, click their cameras with big lenses and then go away. Since such instances happen regularly during the tourist season, the ‘exotic’ Konyak will naturally feel demeaned. But then one of the main reasons tourists come is to Mon is to see the ‘exotic’, formerly-naked Nagas and every tourist –foreign and domestic – is not so sensitive and ‘civilized.’ There is the problem of walking a fine line here. In this regard local tour guides have a lot of responsibility to inform the Nagas as well as the tourists.

There were other villages that I visited but for now I shall go on to give some suggestions to the Tourism department and the Naga villages frequented by tourists.

Suggestions:

1. The State Government with the North East Zone Cultural Centre and the Shangnyu villagers have done well to preserve the piece well as a heritage. Instead of just “any donation” (some unsuspecting tourists were told to ‘donate’ a certain amount), the villagers could do well to charge a certain amount as an entrance fee that even domestic tourists can afford and also place a box inside the museum for goodwill donations. I have no problem in paying some kind of fee for the maintenance and upkeep of the heritage museum, but the fee system has to be done better. The Angh’s son was honest enough not to receive the donation. “If I get it, I will spend it anyhow,” he said and was happy that the donation was given to his mother. I actually wanted to find out the arrangement for the management and utilization of the donations - if all the donations were going to the Angh or to the Village Council or a Trust – but couldn’t because the Angh was not well.

2. Asking money from tourists should be discouraged. It will only give a negative image of us. Instead of following tourists all over the village to sell an item, we should encourage the people to set up small shops where replicas of important artifacts or newer artifacts can be sold. This will also give some sort of self-employment to the people. Some kind of mechanism has to be put in to check selling of important heritage artifacts, e.g. the woodcarving piece lying outside near the eastern entrance of the morung where the new logdrum is kept at Lungwa. Villagers need to be conscientized about the value of these artifacts.

3. The Anghship is an important institution among the Konyak Nagas, and the Anghs, as chief of the village(s), are held in great respect by the people. For most tourists, the Angh is just another object of curiosity. Some of the tourists will not be respectful of the Anghs and this important Naga institution. At each Angh’s house that tourists visit, the Angh can designate someone to be a tour guide. Instead of asking donations from tourists, some kind of nominal (entrance) fee can be charged for a tour of the Angh’s house. The Anghs’ dignity should be maintained; they should not be made into cheap tourist objects. If tourists want to meet with an Angh, besides the tour of the Angh’s house, it should be done only with some sort of an appointment or permission. In such cases, as in the Konyak custom, tourists should be encouraged to present the Angh with a gift, however small, as a token of respect and honor.

4. We should educated our people to be genuinely courteous and welcoming to the tourists. After all, don’t we Nagas pride ourselves to be hospitable people? This same hospitality should be extended not only to the tourists – foreign and domestic – but also to the tour guides. Remember, the tour guides are the ones who bring the tourists (and their money) to our society. Nagas tend to give a preferential hospitality to Western tourists and be indifferent to domestic tourists and tour guides. This kind of bad habit should be stopped. Our hospitality should have no color barriers.

5. If there happens to be a festival going on, such as the Aoleang, it would be a very Naga custom to invite even the tourists to share in the community meal. Those are some of the ‘exotic’ experiences that they will live to tell.

6. Tourists may read about the Nagas before they come to Nagaland, but don’t expect them to know all about our customs and culture. If some of them over step their boundary, explain to them politely there and then. In that way, there are no grudges harbored. Many of them will be thankful for informing them of our customs.

7. To the Naga tour guides and hotel operators, I’d suggest them to go at least to Bangkok (cheaper than going to Bombay or Delhi from Nagaland) and learn how the hospitality industry in Thailand operates. As of now, our claims for Nagaland as a tourist haven are rather pretentious.